Fearing rubbish in the Barents Sea

Here are the governor's horror pictures. Now scientists fear there is also an enormous garbage swirl in the sea out from Svalbard. Maybe even garbage islands.

Denne artikkelen er mer enn 10 år gammel.

"There are more animals each year that must be euthanized, but it varies some and that is not all we come across."

Guri Tveito, head of the Department for Environment Protection for Svalbard's governor, has found examples of animals that have gotten caught in the garbage on land and sea in Svalbard. Several of the photos depict long suffering because the animals have not managed to get loose. The pictures show seals and reindeer are drowned or suffocated by fishing gear or cables, and birds have starved to death because they are tangled in nets and ropes.

Seventeen full truckloads

"We kills around ten animals a year for various reasons," Tveito said. "So we try set free those we come across, at least those who are suffering or will not feed themselves."

About 150 cubic meters of garbage is cleaned up annually from the beaches of Svalbard. It represents about 17 full truckloads and poses a major problem for wildlife, people and the environment. Experience shows quite clearly where the waste comes from.

"The main source is the fishing industry," Tveito said. "It is very much yarn and nets, rope, strapping, fish boxes, plastic jugs and the like."

This is waste that has long persisted (see separate fact box).

In addition to the animals getting stuck, and old nets on the seabed continuing to post a threat to fish and other marine animals, many animals also have large amounts of plastic in them. The results of a survey presented last December by Svalbardposten show 90 percent of all fulmars autopsied had plastic bits in their stomaches.

"We were certainly surprised when we heard it and it is worrying," Tveito said. "What it means for the population here, we hope researchers will find out."

Increasing

So-called microplastics are everywhere, including the sea ice, a new study shows. When the ice melts small fragments are released and ingested by animals.

"It is clear that this can have consequences for marine organisms," said Geir Wing Gabrielsen, a researcher and leader of the research on contaminants at the Norwegian Polar Institute.

International studies show that if, for example, fulmars have more than 0.1 grams of plastic in their stomachs, it begins to affect food absorption and the physiology of the bird.

Research in Svalbard show that 25 percent of fulmars are above this threshold set by the OSPAR Commission (see fact box).

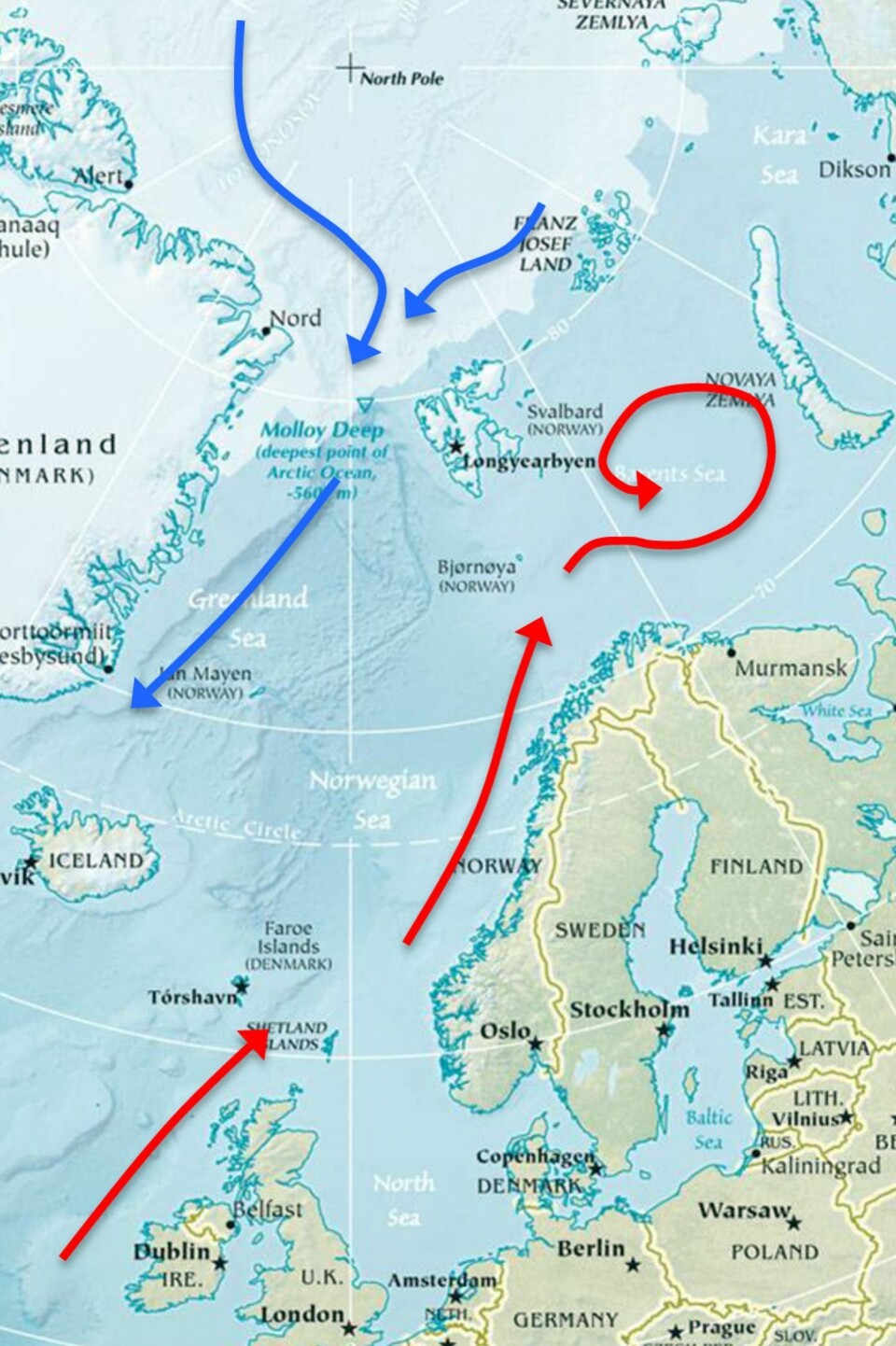

"The values are higher in Iceland and the Faroe Islands than in Svalbard," Gabrielsen said. "Further south in the North Sea and the English Channel the value is up to 70 percent. There is reason to assume that this value will increase in our area in the coming years."

Trash vortex

At the same time scientists fear an enormous trash vortex is building up in the Barents Sea. Plastic waste degenerates and becomes microplastic vortexes, known as gyres. There are five such collections in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans. A gyre is a vortex in the ocean that is largely driven by the wind, allowing the waste to drift around and around on the sea surface until it sinks or washes ashore. In these gyres there will form islands of garbage. Researchers fear such a gyre is about to form in the Barents Sea between Svalbard, Finnmark and Novaya Zemlya.

IN ADDITION: Research rubbish gives headaches

Gabrielsen see the worst case scenario being a permanent trash vortex – a collection point – in the northern Barents Sea. The problem is that the garbage at sea does not have a specific address since the trash is in an international body of water.

"Predictions suggest that the Barents Sea will be the sixth gyre," Gabrielsen said. "It is important to investigate this further."

Recently he gave a lecture to the staff of Norway's Ministry of Climate and Environment about the plastic problems in the oceans. At a United Nations meeting in Nairobi in late June, Climate and Environment Minister Tine Sundtoft stated Norway will step up the fight against pollution of the oceans.

"You think you have a similar problem in the Barents Sea and that means this garbage must be collected," the researcher explained. "In addition, we do not know what the consequences of plastics on the seabed will be for marine organisms living in the sediments."

What he knows in the meantime, however, is garbage and plastics in the marine food chain is a growing problem. It is not long since plastic was discovered in the stomachs of 20 percent of the snow crabs investigated in connection with a research expedition in the Arctic.

Clearing cruise soon

The governor's annual cleaning expeditions in Svalbard begin in July. The cruises are divided into two parts with a cleaning crew change so that as many inhabitants of Svalbard as possible can join in. There is additional clearing during other expeditions, while the cruise industry contributes to cleaning the beaches as they take groups of tourists there.

But the ocean is full of junk that drifts around and some finds its way to Svalbard's beaches.

"From when a beach is cleaned, it takes about six years before it is refilled," Tveito said. "Nonetheless, it is a meaningful thing to do."

"The very best would be if man stopped throwing rubbish into the sea. Otherwise, there is not much else one can do but clean."