Wildlife of Svalbard under a 'climate whip'

Mild and wet winters make life for the hardy species on Svalbard's tundra difficult. Rain on snow turns to ice on the ground and forms an armor against the vegetation that plant-eaters live by. The fine interplay between species on the tundra changes and the animals die.

During Svalbard's overwinter there are only four warm-blooded terrestrial animals. The animal society is composed of two native species (reindeer and ptarmigan), a locally introduced population of east voles and – as predators and scavengers – arctic foxes. In the summer the tundra supplies large amounts of arctic geese (pink-footed and barnacle) and other ground-nesting birds like the snow bunting and waders. When conditions are normal there are also glaucous gulls and skuas as predators and scavengers that eat eggs from birds that nest on the ground. The terrestrial ecosystem is simple and consists of a few species with a dense, unique coupling to the marine ecosystem. The land ecosystem in Svalbard is well-suited for studying the interactions between species – for example, between plants and plant-eaters and between prey and predator – and the natural environment.

'Reindeer's death – fox's bread'

In Svalbard reindeer must withstand up to nine months of snow cover and limited food availability. Studies have shown that mortality rates vary between years and are largely determined by the density of reindeer and winter conditions. A high mortality rate of deer one winter is usually followed by lower mortality and fewer carcasses the next winter since reproduction and competition for grazing decreases. In wintertime the reindeer carcasses make up an important part of the arctic foxes' diet, and a positive correlation has been found between the number of carcasses available on the tundra and the arctic foxes' reproduction and population size. A large supply of carrion gears up more arctic foxes for a subsequent summer that may increase predation pressure on ground-nesting birds. In this way, Svalbard's reindeer are probably a significant indirect influence for many other species in the tundra ecosystem.

Under the climate whip

Mild winters with the subsequent formation of a thick ice layer on the tundra affect the growth rate of all four wintering species negatively. The whip's end is mild periods with rainfall leading to a coat of ice and reduced food availability. The three plant-eaters – Svalbard ptarmigan, Svalbard reindeer and voles, with their very different body sizes, mobility, longevity and reproduction – get a stock blow proportional to the rainfall. While the stock decline of plant-eaters comes in rhythm with the winter rain, the decline in the fox population comes after a one-year delay. This is due to a reduced availability of reindeer carcasses the year after a rainy winter. This synchronous and very clear response for one and all wintering species is probably due to rainy weather occurring especially powerfully and frequently in Svalbard during the winter and that this simple, high-Arctic tundra ecosystem is controlled by a few important relationships.

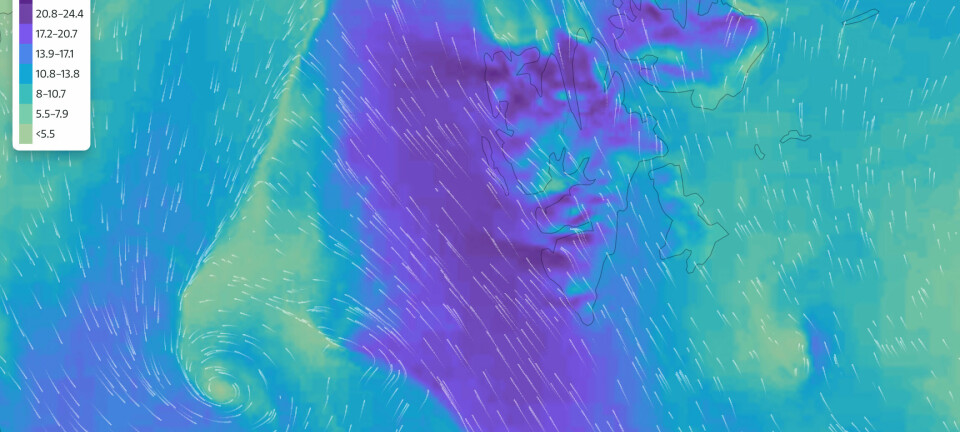

Svalbard is getting warmer

The climate of Svalbard is changing. Summers and winters have been wetter and warmer. The number of days with rain during the winter has increased and there are fewer days with extreme cold in winter. In Europe, it is actually Svalbard that has experienced the greatest average temperature increase during the past 30 years. Future climate scenarios for Svalbard describe a likely temperature rise of approximately three degrees Celsius in the south and up to eight degrees Celsius in the northeast from the period of 2071-2100 compared with 1961-1990. The biggest changes are expected to occur during the winter with frequent rain and subsequent ice on the ground. Climate warming may also lead to an earlier start of spring and a "greener" Svalbard. These changes can have a direct effect on the plant community's composition, growth and biomass. Such changes may, for example, better the livelihood for the largest plant-eater, the Svalbard reindeer, and might counteract or buffer the negative effects of rain during the winter. The net effect of both mild and wet winters and hot summers on the animal community is little studied so far.

Long biological time series required

A long biological time series is needed to understand how climate variability affects animal communities. In Svalbard, the Norwegian Polar Institute annually monitors the arctic foxes, reindeer and ptarmigan. The species are monitored because they are an important part of the food chain in the tundra ecosystem. In addition, they are hunted and both grouse and reindeer are native species, meaning they exist only in Svalbard (Svalbard ptarmigan are also reported from Franz Josef Land). Each year the data is reported into the Environmental Monitoring System for Svalbard and Jan Mayen (MOSJ), where there is information about the species and their population trends (www. mosj/npolar/no/no). The researchers have combined and analyzed surveillance series of grouse, reindeer and foxes, and gained unique insight into the impact of climate variability on the animal community. The findings (see the paragraphs above) would not have been possible without the long biological time series that provides information about species and populations that have lived under different weather conditions in Svalbard. Monitoring the series is therefore necessary to detect the effect of climate variability.

KOAT - a unique initiative

The Fram Centre has recently launched a comprehensive science plan for a "Climate Ecological Observation System for Arctic Tundra" (KOAT; www.framsenteret.no). KOAT shall extend the existing monitoring of the tundra ecosystem in Svalbard to include all stages of the food chain – from plants to predators. The observation system will give researchers the ability to detect changes and identify the effects of climate variability on the tundra ecosystem.

This knowledge will provide authorities and managers a better vantage point to document, understand and act in relation to the dramatic climate effects that occur in the Arctic.