Church bells, coal and climate

The parish priest in Svalbard wishes politicians would look to the Svalbard Environmental Act when allowing northern oil exploration in the Barents Sea. At the same time, there is a calling for him to pray for Store Norske.

Denne artikkelen er mer enn 10 år gammel.

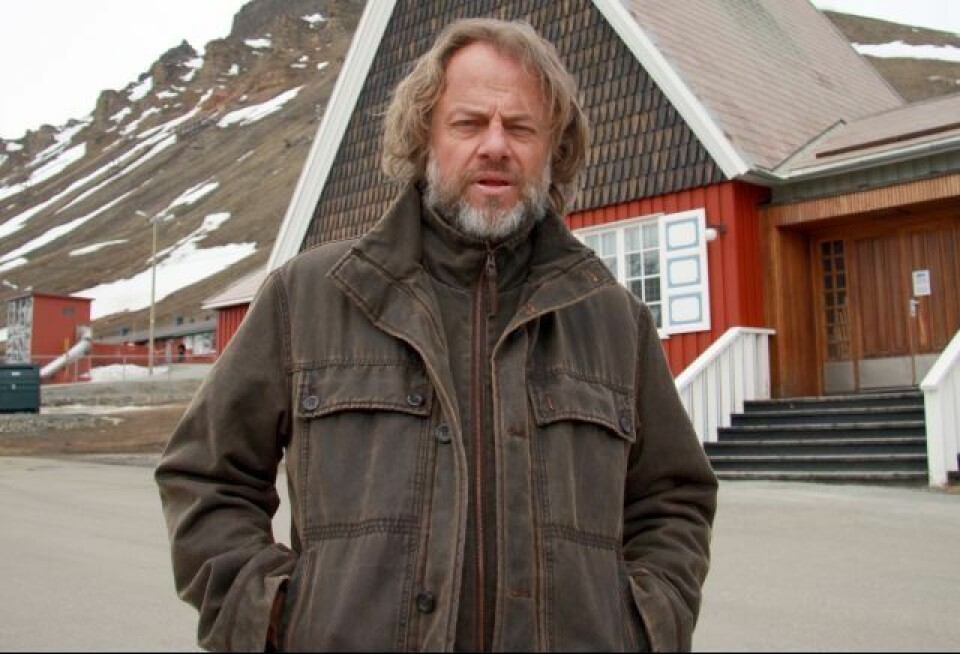

"We don't just say 'hallelujah' and celebrate ourselves," said Svalbard Church Priest Leif Magne Helgesen.

The climate issue is important for the leader of the world's northernmost church and the 50th anniversary of the church in 2008 was a good opportunity to embark on a long-term effort.

The ice is melting

"We are a church where the ice is melting, but where we also rightly focus on the global changes of climate justice as a fundamental concept," he said.

On Sunday, World Environment Day, he will convene his congregation on a hillside outside the church for a climate worship. The nave will be replaced by one of the old cable car towers from mining activities in ancient times. The service marks the start of Klimapilegrim 2015, a national walking tour through August that is part of an international climate pilgrimage leading up the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris later this year.

"The main message is to demand that Norwegian politicians must take responsibility for combating climate change," Helgesen said. "We live in the rich part of the world that has done most to create the negative climate change, but the world's poor are the hardest hit. Therefore, we at Svalbard Church put a focus on climate justice and challenge Norway to contribute more money to mitigation in poor countries, and focus more on treatment and less consumption."

Precautionary

The priest has distinguished himself on climate issues and was one of the authors of the book "The Ice is Melting - Ethics in the Arctic," published earlier this year in Norwegian and just released in English. In recent days, he has hosted offshore priests and led the Seaman Church, and together they organized the seminar "Ethical Reflections on Oil and Gas Exploration in the Arctic."

"The church engages itself, and as a church we shall be with and speak out when life is threatened," Helgesen said. "At the same time, we will also ask questions and create a sense of curiosity and a dialogue, and not always come with the answers."

What does he think about oil activity outside Lofoten and north toward Svalbard?

"When it comes to the birthplace of fish, we are clear," he said. "In the Barents Sea it is not carte blanche, but there are greater opportunities. The Svalbard Environmental Protection Act is the world's strictest environmental protection, and we also need a precautionary agreement beyond the 12 mile border."

What about allowing activity at the edge of the sea ice as it diminishes?

"This is the more political question, but it is important that we not only move on a limit, but also follow up with legislation and protect our descendants' interest," Helgesen said. "Then it is not about one ice edge, but about life being threatened."

The ice edge, the boundary where there is more than a 30 percent probability of sea ice, formed the absolute northern border when the management plan for the Barents Sea was crafted in the early 2000s. This boundary has since shifted due to higher sea and ice temperatures. The debate over oil in the north accelerated again when the government wanted to move the permissible limit for oil and gas in the Barents Sea further north, extending to the same northern latitude as Bjørnøya. The island is part of Svalbard and Helgesen therefore asserts Norway has a moral responsibility for an even stricter regime.

Prayers for coal

The term "climate refugee" is new and did not exist as a concept when Helgesen was doing humanitarian work in the early 2000s. Today it is part of everyday speech. He warmed up to climate worship with the declaration the countries consuming the most and producing the highest emissions must take responsibility. The poor are the most vulnerable to human-induced climate change.

Recent summits have not resulted in new agreements, but the priest said he is hopeful about the Paris summit in December. Achieving an international agreement is like a big oil tanker – it takes time to get it to change course, he said.

"We who are up here have a very special opportunity," Helgesen said. "Svalbard Church is the northernmost and as the world's northernmost religious leader I have a responsibility to speak out when life is threatened."

But at the same time, he is requesting prayers for the crisis-hit Store Norske. The coal company announced before Christmas it was terminating about 100 of its 340 employees and is awaiting Parliament's approval of a 500-million-kroner bailout package. The company will operate at half capacity during the next 18 months and determine in 2016 if it is practical to reopen the Lunckefjell mine. If not, the result may be more layoffs.

Many affected

Wenche Ravlo, Store Norske's administrative director, wrote an article in this week's Svalbardposten stating the company's goal is to deliver refined coal to new customers by next year.

"Store Norske's goal is still coal mining in Lunckefjell after 2016 as well, assuming our own costs and market conditions make this possible," she wrote.

"Store Norske is a cornerstone having difficulties and changes are taking place," Helgesen said.

"Personally, I am not averse to Store Norske and mining, and I think the big challenge will be oil and gas outside Svalbard. That will have greater consequences than a little coal dust on the mountainside. But coal on a global scale is a challenge. We need to develop new treatment technologies and switching over to gas that has lower emissions."

Yet he is praying for Store Norske?

"Yes," Helgesen said. "Store Norske is important for people and our presence. We see that individuals and families are affected, and it does something to us as a community. It is about showing solidarity."

Can that be seen as hypocritical?

"By all means. Coal has an economic and climatic end. We are seeing that now, but if it takes five or 20 years to end we do not know," said Helgesen, emphasizing he believes the government erred by not supporting a carbon-capture storage facility to reduce pollution from Longyearbyen's coal-fire power station.

"Had we done that, we would have given a gift to the world," he said.

Translated by Mark Sabbatini