Svalbard Treaty at 90 years – a success story?

In addition, he managed to provoke the Norwegian authorities into giving him the reaction and attention he wants.

Much has already been said about Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin's surprise visit to Svalbard on April 18 of this year. The man is on the European Union's and Norway's list of undesirable persons for his role in connection with Russia's annexation of the Crimean peninsula just over a year ago. He was nevertheless able to emerge in Svalbard, provoking Norway's Ministry of Foreign Affairs so thoroughly the Russian ambassador was summoned to provide an explanation. State Secretary Bård Glad Pedersen announced a rule change will be sought to ensure persons on the sanctions list in Norway are also denied access to Svalbard. Various commentators and researchers have warned that Russia is challenging the Svalbard Treaty and Norway's sovereignty in the archipelago, and that the conflict may

Symbols

Ninety-five years ago, in 1920, European leaders met in Paris to discuss what the continent should look like as a result of the dramatic upheavals in the wake of World War I. The numerous treaties and agreements signed are now history, as they say, but with one exception: the Svalbard Treaty. The treaty gave Norway "full and unrestricted" sovereignty over Svalbard, but recognized free access, and the right to operate commercial and certain other businesses for citizens of all countries that had signed the treaty or acceded to it since. The treaty has no time limit and is therefore applicable "forever," at least as long as it is not being challenged – by Norway or others.

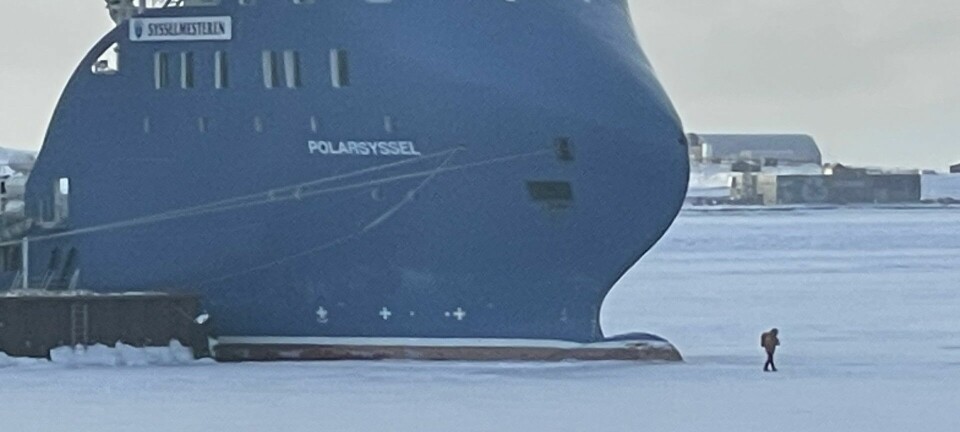

That Russia has "historical rights" in Svalbard is something we are constantly reminded about by Russians. The claim is well-founded: the Russians were the first to start overwintering in Svalbard in the early 1700s and were so adept they reigned supreme in the area for about 150 years. And since the 1930s, the Soviet Union/Russia has been the only major player in Svalbard beside Norway. For both countries, there has been consistent politicking and claims that maximize elbowroom for themselves, combined with the greatest possible limitations for the other party. In other words, it has been Norway's policy to maintain – and if possible increase – its sovereignty in the area, balanced up against relations with the powerful neighbor to the east. For the Soviet Union it was imperative to ensure their rights, keep as free a position as possible and ensure Norway didn't established military structures in Svalbard in violation of the treaty. Today it seems contemporary reality has produced some peculiar results: due to Soviet opposition it took decades before a proper airport was built in Longyearbyen, and even visits by the Norwegian Coast Guard to Svalbard were considered controversial. The Soviet communities lived their lives very well outside of Norwegian control. It was symptomatic that The Governor of Svalbard had a permanent office in Barentsburg, but had to stick to a cabin with accommodation space and meeting rooms at Finneset just south of the settlement's "city limits." Since the 1970s, and increasingly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Norwegian government has gained an ever-wider catchment area and, around 1990, Norwegian road signs and letter offices in the Russian settlements – two important symbols for sovereignty claims.

Like the rest of the kingdom

The treaty requires equal treatment for all citizens of signature nations in Svalbard. In practice, Soviet – and later Russian – citizens have been exempted from a number of laws. The Svalbard Treaty, in principal, allows discrimination of Norwegian citizens vis-a-vis those who are foreign. But a Russian in Barentsburg must be treated under the same principles as a German in Longyearbyen, to cite an obvious example. Our goal is that all the laws and regulations applicable in Svalbard must apply equally to everyone residing in the archipelago, wherever and whatever their nationality. Put simply, we can say the understanding of "equal treatment" has gone from applying non-interference in the foreign (Soviet) settlements to include individuals and corporate rights and responsibilities. The principle is now uncontroversial and, moreover, hard to argue against. Increasingly frequent visits to Barentsburg by Norwegian authorities – including the Environmental Agency, Labour Inspection Authority and the Food Safety Authority – are accepted and their remarks are largely taken into account. Today, fortunately, the governor or any other Norwegian authority representatives are welcomed with broad smiles and open doors in Barentsburg, both by the mining management and the Consulate General. In so far as the treaty permits, the goal is that Svalbard will be managed the same as the rest of the kingdom; However, the situation is such that Norwegian laws apply in Svalbard only when explicitly mentioned in the law.

NATO fears

The gradual expansion of the Norwegian government has not always been trouble-free. The Svalbard Environmental Protection Act of 2001, representing a dramatic expansion of Norwegian administrative practice and law, met immediate and strong protests from the Russians. According to Moscow, the Svalbard Treaty was in practice set aside with the new law's requirement that environmental considerations should always weigh heaviest. Article 3, which gives all signatory citizens the right to operate "unimpeded in all manners of maritime, industrial, mining and commercial on completely equal footing" is undeniably something hollow all the time, plus the entire archipelago outside the settlements has been turned exclusively into a large conservation area. The Russians also felt the Environmental Act's ultimate purpose was to push the Russians out, not to protect the environment. The basis of their argument was Barentsburg was far more dependent on coal mining than Longyearbyen – an interesting point of comparison considering the current debate about Store Norske's future. Even liberal politicians in Moscow feared that Norway's intention was to establish NATO bases on Svalbard once the final miner had left Barentsburg, which shows a quite different picture of reality than what we are used to. The Russians are undoubtedly right that the environmental law is an important political control instrument and an effective way to restrict commercial activities in Svalbard, but the limitations also apply to Norwegian players. One need not look far in Longyearbyen to find critical voices against the environmental law; those interested can take a walk up to the leadership of Store Norske, for example.

Customization

While Moscow complained about Norwegian infringement, activity in Barentsburg was steadily on the decline. The decay during the early 2000s was so massive that officials from Moscow was embarrassed over the grotesque wealth gap that had developed between Barentsburg and Longyearbyen. After a series of embarrassing episodes involving the management at Trust Artikugol, the need for changes were pressed forward. A government commission was appointed to look at the circumstances and its leader Sergej Narysjkin, the deputy prime minister at time and current head of the State Duma, made a number of statements during his visit to Svalbard in 2007. Barentsburg, he said, should learn from Longyearbyen, the economy should be diversified, it should focus on tourism and research, and the government's task would be reduced to providing the necessary infrastructure. Trust Artikugol's new management has implemented a number of impressive – and essential – measures in the mining community, which appears to be far more modern than just a few years ago. It is growing, albeit slowly, in both tourism and research. But whether there is political will and, more importantly, the financial capacity to develop alternative livelihoods remains to be seen. That mining in Barentsburg sooner or later will have to cease in any case is a certainty - and it is completely independent of the Norwegian environmental authorities.

Responding as hoped

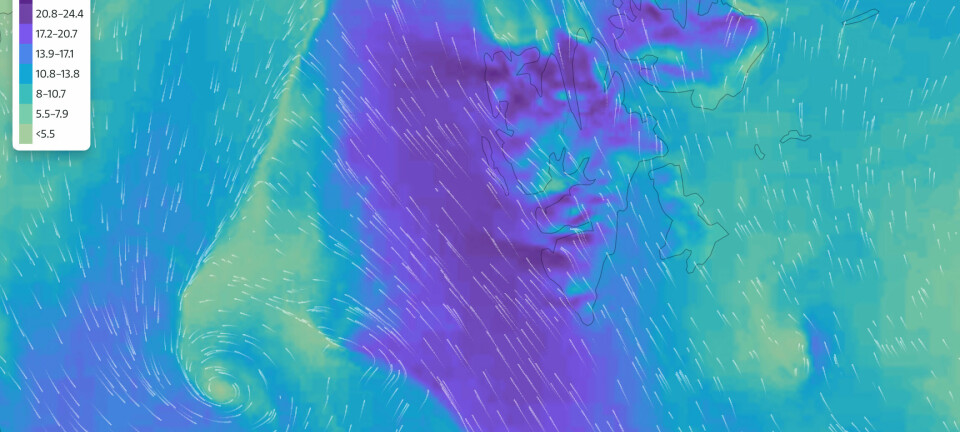

While relations between Russia and the West in general are at a freezing point, in Svalbard it's largely business as usual. Until Rogozin's visit a couple of weeks ago, prompting Aftenposten to declare in an April 20 editorial "(the) Russian minister's visit to Svalbard is a provocation that highlights new challenges in the north." Dag og Tid wrote in an editorial the visit shows how sensitive the Svalbard Treaty is. That Rogozin wanted to provoke is obvious – such a desire underlies most of his work. But his visit was no challenge to the Svalbard Treaty, nor against Norwegian sovereignty. The visit was a challenge against the sanctions we and the EU have introduced against him and several other centrally-placed Russian officials. The penalties are extremely unpopular in Russia and every poke at the West is well-received by the Russian public. In addition, he managed to provoke the Norwegian authorities into giving him the reaction and attention he wants. Because if Rogozin is denied access to Svalbard in the future, it will for him be completely irrelevant: he hardly likely to envisaged himself in Svalbard in the first place (and there is no reason to fear a rush of other Russian people considered non grata arriving in Svalbard). Conversely, Russia is getting a good opportunity to protest against the Norwegian enforcement of the Svalbard Treaty and as a matter of principle. The treaty is hardly so fragile and sensitive as some Norwegian commentators seem to think, but it would be rather foolish to provoke a conflict with Russia on this basis. If Norwegian authorities want tranquility surrounding our management in Svalbard they should therefore put this issue to death sooner rather than later. For the high degree of trust Russia generally has in the Norwegian government of Svalbard is, from a historical perspective, both gratifying and sensational.